Nearly six decades later, the same ethnic fault lines continue to define DR Congo’s conflicts. The resurgence of the M23 rebellion, led by Congolese Tutsi who share ancestral ties with Rwandan Tutsi, mirrors the historical exclusion of Banyarwanda from Congolese identity

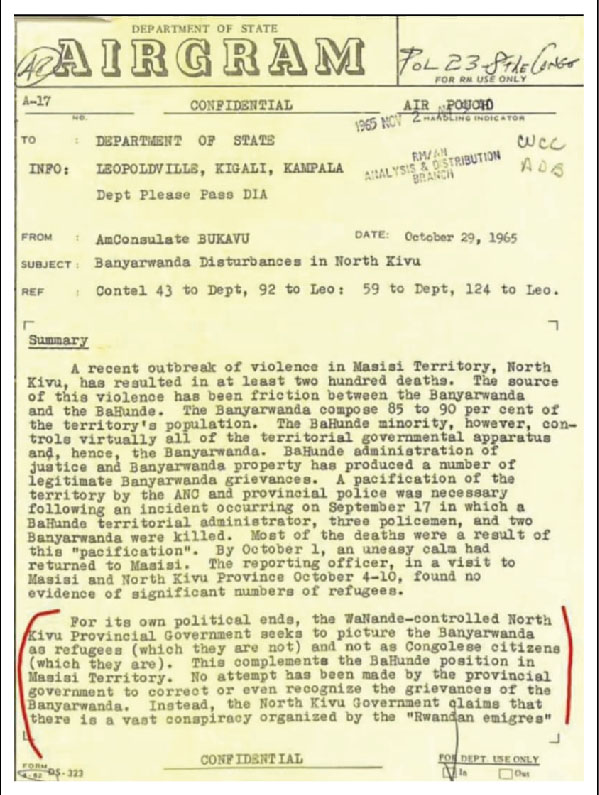

A newly surfaced confidential document from the United States Department of State, dated October 29, 1965, reveals that the North Kivu provincial government sought to portray the Banyarwanda population as refugees rather than Congolese citizens.

The airgram, sent from the American Consulate in Bukavu – current capital of South Kivu in Eastern DR Congo – to Washington, details violent disturbances in Masisi Territory, North Kivu, where friction between the Banyarwanda and the Bahunde led to at least 200 deaths.

Keep Reading

- > Museveni, EAC leaders call for “immediate” ceasefire in DRC

- > Kagame Blasts Ramaphosa as Dishonest, Dares SA to Military Confrontation

- > Over 280 Romanian Mercenaries Surrender to M23 in Mineral-Rich Areas of North Kivu

- > South Africa’s Ramaphosa Calls Rwandan Army ‘Militia’

The document states that while the Banyarwanda made up 85 to 90 percent of Masisi’s population, the Bahunde minority controlled nearly all aspects of the local government.

The Bahunde administration’s handling of justice and Banyarwanda land disputes led to growing grievances. The unrest culminated in deadly incidents on September 17, 1965, when a Bahunde territorial administrator, three policemen, and two Banyarwanda were killed.

The ensuing crackdown by the Congolese National Army and provincial police resulted in further deaths, with authorities describing it as a “pacification” effort.

Despite the violence, the American official who visited Masisi and North Kivu between October 4 and 10 that year reported finding “no evidence of significant numbers of refugees.”

However, the airgram highlights that the Nande-controlled provincial government was actively pushing a narrative that classified Banyarwanda as refugees.

“For its own political ends, the North Kivu Provincial Government seeks to picture the Banyarwanda as refugees (which they are not) and not as Congolese citizens – which they are,” the confidential cable recently declassified, says.

The document further reveals that the government had made no effort to address Banyarwanda grievances. Instead, officials in North Kivu justified their stance by alleging a vast conspiracy led by “Rwandan émigrés.”

This position aligned with that of the Bahunde leadership, which opposed recognising Banyarwanda as full Congolese citizens.

Nearly six decades later, the same ethnic fault lines continue to define DR Congo’s conflicts. The resurgence of the M23 rebellion, led by Congolese Tutsi who share ancestral ties with Rwandan Tutsi, mirrors the historical exclusion of Banyarwanda from Congolese identity.

The M23, which on Monday captured Goma, accuses the Kinshasa government of perpetuating genocide against their community and deliberately alienating them from national belonging.

The M23 say they will no longer pull back from Goma with their political leader Corneille Nangaa on Thursday telling the media that they are determined to establish a new government or push further into Kinshasa if provoked.

Much like in 1965, Kinshasa today continues to brand M23 as a foreign-backed movement and labels Congolese Tutsi as Rwandan refugees rather than citizens.

As the conflict intensifies, the 1965 airgram offers a stark reminder of the deep-rooted nature of the crisis—one where identity and belonging remain fiercely contested in North Kivu.